I gave this short talk on May 17th at Slack HQ for the SF Slack Developers’ Meetup. The video is on Ustream — my segment starts around 3:30. But if you’re not a video person, here’s the script I wrote beforehand, and you can check out the slides here.

Hi, my name is Sonya. I run a community Slack group called Cyberpunk Futurism. It’s pretty lively — last time I checked there were more than ninety members, about half of whom are active. We discuss technology, economics, the current and future dystopia… You know, whatever. Small talk.

Roughly ten members hang out almost every day. Depending on the size of your company, that might seem small, but Stewart Butterfield mentioned in 2015 that the average Slack team has eight or nine members. I don’t know if that’s mean or median average, but there you go.

As the admin, I’m the main person who installs integrations and bots. I usually go through Slack’s directory, and I’m often looking for something specific. For example, recently I wanted an integration that would do what Giphy does, but pull from static images. It doesn’t exist, by the way — hot tip for one of you, in case you want a totally non-monetizable idea. We also have a Github integration, the Twitter auto-expander, and so on.

I want to give my community cool tools to play with, and utilities that allow us to collaborate creatively. There’s a lot of stuff in between me and that goal. I have to look for the tool, go from Slack’s directory to the landing page, click install, select a team — there are a lot of steps, each of which is a potential drop-off point. Hopefully Slack will have a full-fledged app store at some point and installation won’t be such a pain.

Anyway, the members of my Slack community are a bunch of paranoid technophiles who value their privacy. I take that as seriously as Slack’s free settings will let me. A business that has confidential discussions in Slack will take it even more seriously, and they’re going to hesitate to assume any risk.

Most Slack integrations don’t come from comforting IT name brands like Microsoft or Apple. It’s some upstart little company. Trust me, I love upstart little companies, but I don’t have time to run a background check on all of you. Because you’re an unknown quantity, that represents risk. I don’t know exactly how your integration works, how it stores the data it collects, and I definitely haven’t read your EULA, so I’m likely to err on the side of caution.

Uncertainty introduces fear — sometimes the fear is irrational, and sometimes it makes sense. There are all kind of things that users “should” or “could” do, most of which they will totally ignore. People are busy and they have different priorities. Think of users as timid baby bunnies who are simultaneously running a company.

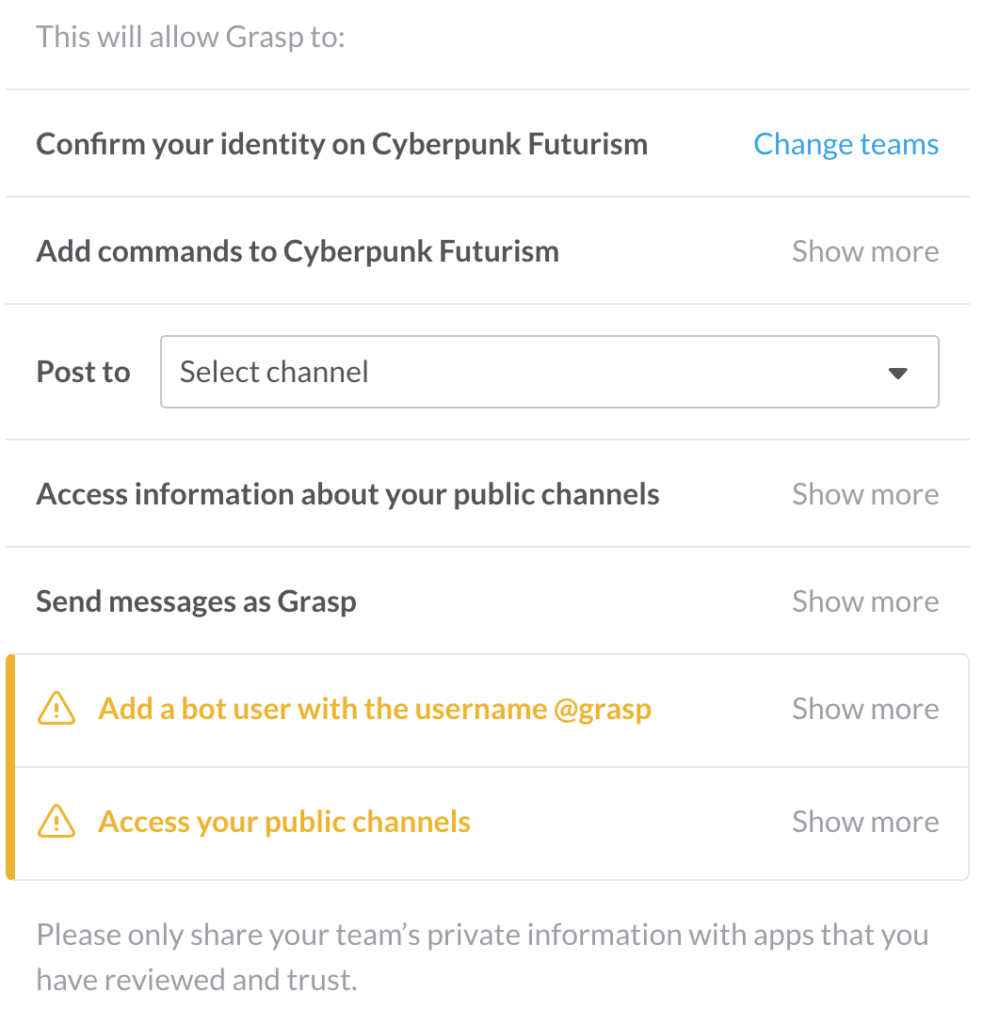

Anyway, the screen that I pause on the longest is this one — the one where Slack tells me what kind of access the integration is asking for. Usually it’s asking for more information than seems reasonable. Most crucially, I don’t know why.

Remember to look at this from the user’s perspective. I am indifferent to your goals unless they align with my goals. I have nothing invested in your integration in particular. My cost-benefit analysis involves the safety of my community, and that counts for way more than your KPIs. It probably also counts for more than my desire for another unproven productivity enhancer.

All of this is a very long windup to say: tell me on your landing page why you’re going to need the amount of access you need. If you’re going to ask for access to all my channels and user data, you should explain why that’s necessary, and call out your privacy policy. Most likely I won’t actually read your privacy policy, but when you mention it, that soothes my lizard brain.

So those are the problems I face whenever I’m considering a new integration, and they pose problems for you too. Because you want me — or rather a manager at some company with tons of money to burn — as a user.

Of course, you should A/B test all of this. Maybe I’m totally wrong, or you’re selling to a weird market, and doing permission priming will repel your potential users. But at least think about trying it out. Maybe have a couple of different landing pages where you can funnel different types of users.

After installing an integration, I’m usually still not sure how to interact with it. Give me a rundown of the basic actions and how to adjust settings. Don’t surprise me by popping up in places where I haven’t been told to expect you. If you can do the onboarding directly through Slack, that’s perfect. Otherwise shoot me a welcome email with some instructions for beginners.

I would also encourage you to use slash commands instead of bot users as much as possible. They’re way more intuitive, and much faster for simple tasks. I know some use-cases don’t work with slash commands, but for the ones that do, those are better.

Before I give up the mic, I want to mention one more time that your attitude toward users should be empathetic as much as possible. I’ve worked support so I know users are annoying, but try to reduce your own frustration with their lack of domain knowledge and expertise. Make an effort to understand their incentives.

That’s all! Have fun building!

Nick Babich wrote a great article about permission priming called “The Right Ways to Ask Users for Permissions” that you should read next!